Together with Julian Holloway (Manchester Metropolitan University), I have co-organised a session on The Geographies of Folk Horror for this year’s RGS-IBG Annual Conference, to be held at the Royal Geographical Society, London, 27-30th August 2019.

The session will be held on Thursday 29th August and features the following papers and speakers:

- ‘On the Geographies of Folk Horror’, James Thurgill (The University of Tokyo, Japan).

- Julian Holloway (Manchester Metropolitan University)

-

‘“Wraith-like is this native stone”: folklore, folk horror and archaeological landscapes’, Katy Soar (University of Winchester, UK)

-

‘Horror in (English) Folk Music and the Rise of Eco-Horror as a new Theme’,Owain Jones (Bath Spa University, UK)

Abstracts

1. On the Geographies of Folk Horror, James Thurgill (The University of Tokyo, Japan).

Since the turn of the new millennium, the humanities have undergone a growing engagement with themes of absence, monstrosity, spectrality and, more broadly, the supernatural in its various guises. Human geography too has seen a number of scholars turning to the ghostly, occult and magical in their analyses of spirituality, place and experience. A more recent development that has emerged from these earlier explorations of the strange and uncanny has been the retrospective coining of ‘Folk Horror’, a strain of horror based largely on (mis)representations of pastoral geographies and the people who inhabit them as menacing, malevolent and anti-modern.

In its numerous associated films and texts, Folk Horror has sought to complicate the relations between people and places, offering a horror almost entirely reliant upon the destabilising of the worlds in which its characters (and audience) dwell, often utilising a sense of dread that emerges from beneath the earth itself. In doing so, the fear and the threat that Folk Horror has traditionally evoked has been one derived from the deliberate manipulation of the boundaries ordinarily thought to exist between nature and culture, people and places. Human, non-human and more-than-human actants come together to alter, disturb and delineate space and time.

While Folk Horror’s texts undoubtedly depict, challenge and problematise all sorts of spaces and environments, including the city via the lens of the Urban Wyrd, geographers have almost entirely neglected the genre and its cinematic, literary and sonic outputs in their analyses of popular representations of geography. This paper offers an overview of the geographies of Folk Horror and considers the genre’s ongoing contribution to the popular geographic imagination.

2. Sounding Folk Horror and the Strange Rural, Julian Holloway (Manchester Metropolitan University, UK)

For the most part, the recent interest in all things Folk Horror has been dominated by the visual and the textual. Less documented is the role that folk horror tropes and meanings play in music and sound. This paper seeks to redress this imbalance by thinking through how we might understand folk horror as something sonically articulated and musically constructed. In so doing, exploring the sound of folk horror is often less about representation and more about atmospheres, expressed worlds and certain imaginative geographies. The paper seeks to chart these atmospheres and imagined spaces through examples from a variety of musical and sound artists who variously sonically practice the strange and disturbing rural. These works allow us to consider the role of the landscape itself, affective registers of the eerie, uncertainty and the acousmatic, in the production of folk horror sonics and musical worlds.

3. “Wraith-like is this native stone”: folklore, folk horror and archaeological landscapes, Katy Soar (University of Winchester, UK)

Archaeological monuments and landscapes have long loomed large in the popular imagination, creating as they do impressions of deep temporality, of lingering hint of things broader, deeper, and more ancient than ourselves, which often translates into a sense of unease, or eeriness, if not outright fear. These impressions often manifest through storytelling: traditional folk stories that develop around monuments such as Neolithic stone circles, henges and long barrows talk of petrification, giants and devils. Alternatively, many horror writers of the 19th and early 20th century locate their tales of terrors directly in the archaeological.

What binds these stories together – those of folklore and those of folk horror – is an understanding of the past not as a static entity but as something real, lurking below the surface and waiting to be unleashed. Archaeological monuments act as survivals, physical manifestations of a remote, otherworldly past that is still connected with the present. This paper will consider these narratives of fear which surround archaeological sites by examining both traditional folkloric motifs and the folk horror elements of writers such as M.R. James, Arthur Machen and Sarban. These ‘native stones’, it will be argued, appear ‘wraith like’ because of their ability to destabilise the boundaries of present and past. However, this also allows us to consider how these narratives reflect contemporary understandings of antiquarianism and archaeology as well as contemporary anxieties regarding our place in the world.

4. Horror in (English) Folk Music and the Rise of Eco-Horror as a new Theme, Owain Jones (Bath Spa University, UK)

If Folk Horror has grown in recent decades – it should be remembered that (rural) horror, of one type or another, has long been a staple narrative of folk music. Ghost stories abound in folk song, and weave themes of murder, adultery, betrayals, lost loves, rejected loves, bitter disputes over race, money and property, poverty, into supernatural yarns of the returning dead, of haunted places and landscapes, of fear, longing and suffering. These were songs of, and from, the conditions of the common people rendered supernatural. Some of these narratives, many of them residing in the great song collections such as Cecil Sharp, will have sustained in form for many centuries. They are predominantly rural in setting as they were born of an overwhelmingly agrarian society. They are now being reinterpreted by a new generation of folk artists such as Jim Moray and the Unthanks, often urban located artists, and consumed in urban settings. This longevity is testament to the enduring power of such tales and the melodies they are told through. Citing a number of specific songs, such as the terrifying “Long Lankin”, this paper looks back at this tradition of (rural) folk horror and then explores how new conditions of the common people, such as the horrors of climate change, pollution, and species extinction, are entering the folk music cannon, and speculates on whether they can have similar force as the older enduring narratives of human life, suffering and death, and their shifting rural/urban provenance.

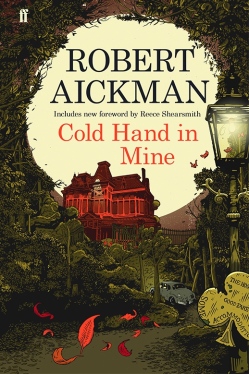

bert Aickman is a master of British horror. His writings are every bit as disturbing as those of other writers in the genre, in many cases I would say they are more so. What makes Aickman’s work particularly unsettling is that he rarely provides a definite ending; the tales themselves are short but often without a terminal narrative. Rather the reader is left in a continual state of suspense and this itself, I believe, proves far more frightening than the horrors described within the text – this sense that they have been created to endure, even after the tale has been read.

bert Aickman is a master of British horror. His writings are every bit as disturbing as those of other writers in the genre, in many cases I would say they are more so. What makes Aickman’s work particularly unsettling is that he rarely provides a definite ending; the tales themselves are short but often without a terminal narrative. Rather the reader is left in a continual state of suspense and this itself, I believe, proves far more frightening than the horrors described within the text – this sense that they have been created to endure, even after the tale has been read.