On Sunday 1st February, Rupert Griffiths and I joined Rob Irving for a guided walk around the mytho-archaeological landscape of Avebury, Wiltshire, as part of the ongoing Public Archaeology project that both Rob and Rupert are contributing to. This was the first time I had visited Avebury and I’ve no idea how or why I have avoided going there before but somehow I had managed to. As those of you familiar with Avebury will know, the entire landscape exists as a series of interconnected earthworks and standing stones and is quite simply staggering to behold. Without question, Avebury is unlike any place I have ever been before and for me, it has an unrivalled sense of wonder; it is peculiar even among other meso and neolithic monumental sites, not least because of the sheer scale of its surrounding henge construction – the largest stone circle in Europe.

Rob’s walk of the area was nothing short of epic, especially given the biting winds and borderline freezing temperatures. Nevertheless, our small but dedicated group made the five and half hour trek from the Waggon and Horses in Beckhampton, up to Windmill Hill, through a series of waterlogged meadows leading the way to Avebury village, across marshy borderlands skirting hillside crop fields to meet Silbury Hill and finally onto West Kennet Long Barrow to see the sun set over the West Country. Each of the sites we stopped at was entirely unique, in terms of both the materiality of the place and the affective workings on the body.

Our first stop, Windmill Hill, held a series of small, grass topped burial mounds, the largest of which we ascended to survey the landscape. From the elevation of this grassy knoll we were able to gain vistas over the entire area. Rob, with his wealth of knowledge of this landscape, was able to map out the features of the ridgeway that lay opposite us, pointing out a line of tree-topped barrows that ran along the ridge. It was evident that each visible feature was situated in correspondence with the next, placed within a zone of interaction so that a sort of placial conversation could take place. The barrows on the ridgeway focused their gaze down upon the henge surrounding the village, whilst simultaneously mirroring our own position atop of the burial mounds of Windmill Hill. Rising from below us Silbury Hill formed a central axis, a verdant spindle from which the rest of the landscape appeared to revolve from.

Rob commented on the placement of the ridgeway barrows, pointing out that they had been placed on the slope rather than the summit and in this sense allowed the ancestors to not only look upon their venerators, but forced the venerators to look back at them. This sense of interconnectedness, of being situated within a sort of topological conversation, belonged not only to the physical features of the landscape but also to us; we too had been coerced by our surroundings into both gazing upon and being overlooked by the earthy tombs that lay on the opposite side of the valley. One could easily become enveloped by the ‘deep time’ that ran through this environment, a sacred milieu that remains of enormous importance to those following the old religion(s) that engage to commune with the natural world. We were fortunate enough to visit Avebury on Imbolc, a Gaelic and (now) neo-pagan celebration of the mid point between the winter solstice and the spring equinox. The village was awash with tethered ribbons and folk adorned in robes and make up, all making a pilgrimage to the ancient stones.

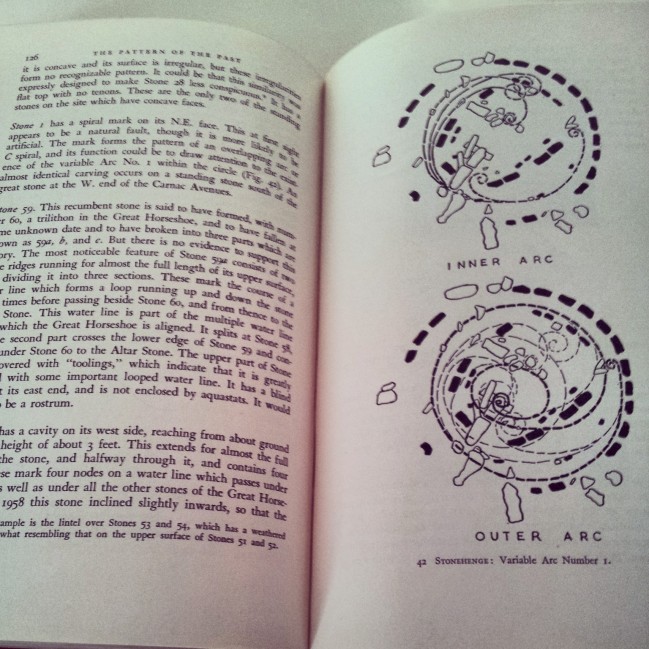

Leaving the village, we followed steps to the top of the henge’s outer ditch bank, turning around to take in the full impact of the immense sarsen columns that created the outer circle. From the peak of the bank we were able to see the remains of the paired standing stones that marked the 1 1/2 mile causeway that led to The Sanctuary, a large circular formation of stone markers that lay at the southern extremity of the village. Briefly stopping to take a few shots of the huge mark-stone couples that formed The Avenue, it was evident just how important mobility was to this landscape. Each site led you to another, forming part of a continuous procession in and between places. One could sympathise with the belief that such movement is symbolic of a traveling between worlds. Indeed, a number of single stones continue to be identified as having mysterious properties attached to them; local folklore tells of encounters with the Devil, increased fertility, of stones moving of their own accord and of disembodied voices, music and shadows emanating from within the stones themselves. Legend is thick in Avebury, it smothers the entire landscape. Its viscosity, if we can speak in such terms, is a result of Avebury’s material presence (the sheer number of standing stones, barrows and mounds) and the extent to which a reasoning behind the placement and purpose of such materials remains largely undetermined, lost to ancient history.

Before entering Avebury, Rob and I had been discussing the largely dismissive attitude that academia has generally taken towards qualitative readings of historical(ly) sacred sites. I made the comment that in fact, of all the academic disciplines, it is Archaeology that has successfully refined the art of ‘storytelling’. Whilst this was said in jest, I do believe there is some truth in the claim. Archaeology works to fill in the blanks that exist between the material fragments of history and the individuals who would once have been attached to them. To this end archaeology works to create and restore narratives, to place things within a storyline that makes sense, historically speaking. I’m aware that this is something of an abstraction but it serves the purpose of questioning why then, archaeology is anymore valid as a means of explicating the past of sacred sites than say, performative art or music? My point is really this; that sensing a place, physically and sensorially engaging with a site, also works to determine a narrative; further uncovering the biography of (a) place. This I believe to particularly hold true of sacred sites.

That ‘legend is thick’ at Avebury, calls for us to not only understand the area historically (through rigorous examination and excavation) but to feel it, to make sense of the links between say the standing stones, the barrows and Silbury Hill, through touch, movement, sight and sound, through becoming immersed in the landscape, by letting it speak to us. I’m aware of a shift in archaeology (as with human geography) towards a more embodied reading of place (Chris Tilley’s excellent A Phenomenology of Landscape springs to mind – a cornerstone text for my PhD) and indeed there has been a sensory and affective turn the humanities in general, but still, it has to be said that spiritual attachments to place, that is those that become the foundation for a ‘deep’ temporo-topological engagement with a site, are still met with much cynicism.

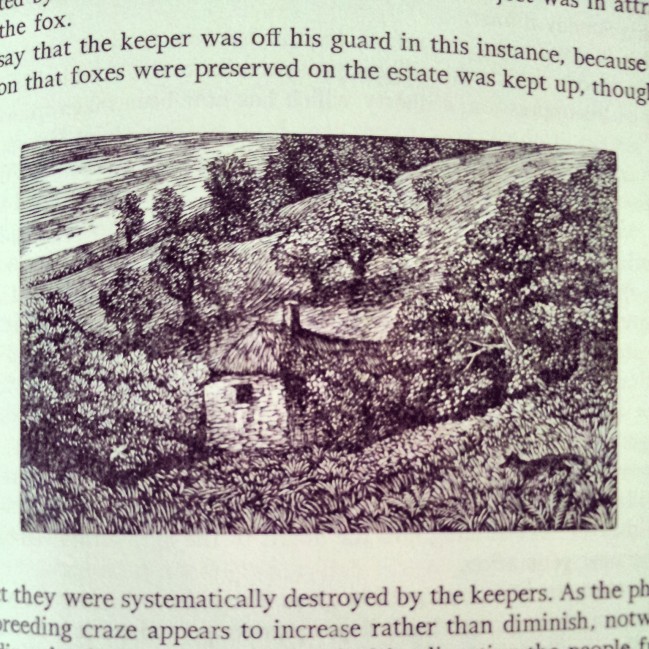

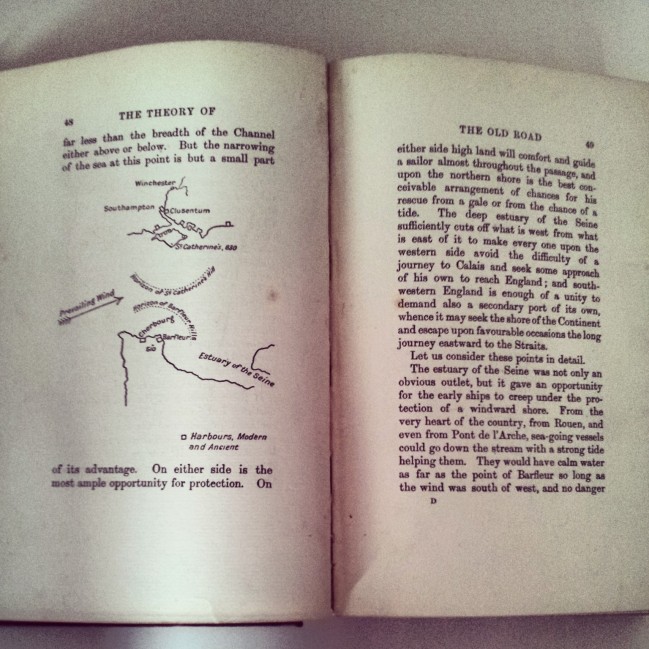

Leaving The Avenue and heading south-eastwards along the A4361, I noticed a tree-topped barrow that marked the edge of the village ramparts. Behind the barrow lay a further two burial mounds (one of which is visible in the image below); all three seemingly in alignment with both the ‘inner’ henge and the mounds situated on Windmill Hill. Viewing the site(s) from this spot reiterated the sense of interconnectedness that the Avebury landscape engendered, demonstrating that these individual sites were supposed to work together, to ‘speak’ to one another through their locative interaction, through a moving in and between them.

Much has already been said about the ongoing desire to mystify this landscape, John Michell referred to the process in his The View Over Atlantis as ‘an aesthetic law which defies formation’. Indeed, the ongoing mystification of the Avebury landscape is heavily reliant on such a process, one that seeks to assert an obscufication of meaning in the strange material forms that adorn the area. This is a view that sees the historical, social and cultural context of this landscape become occulted, hence further necessitating the need to stand within the site so as to commune with it, to discern for one’s self how and what these barrows, mounds and stones exist for.

Moving further along the A road, we took a left, turning onto a footpath that followed the River Kennet southwards towards Silbury Hill. Edging along the side of the river the trees that lined the Kennet’s banks would frequently break, giving views out over the flooded meadowland onto Silbury Hill. Beyond the viridescent agricultural land, Silbury triumphantly rose from flooded marshlands; vast amounts of water had collected at its foot to form something of a moat, an ominous black lake that prevented passage to the slopes of the hill itself from all but one raised crossing point.

Led by Rob, who was still narrating the esoteric history of the landscape as we moved along, our group continued to edge the fields that surrounded Silbury. The closer we came to the hill the more sodden the terrain became. We were forced to clamber over barbed wire fences to avoid the boggy land but this led us to no drier resolution. Gritting our teeth, we marched on, one by one, through the uninviting foot-deep waters of the marsh, stepping on waterlogged tussocks of grass in order to keep just above the thick, mud-covered bottom. Cold, wet and facing a biting wind, one could easily become despondent, but the sight of the hill, now just meters away, and the promise of reaching the burial ground at West Kennet kept everyone motivated. This was hardly an expedition of a saga-like nature but after four or so hours of walking our feet were now soaked, cold and the wind seemed relentless, to me at least. Rob didn’t seem to feel the cold, or perhaps it was just irrelevant to a man who was clearly in his element, trekking ahead to the next stop in the walk.

Leaving the ‘mud flats’, our party joined the relative comfort of the soft verges that followed the A4. From here it was another twenty minutes of walking before we had made our way to the top of a (sprout?) field and reached the final site/sight of the day; West Kennet Long Barrow. Like each of the other places we had visited that day, West Kennet was at once both breath taking and haunting. The construction of this vast Neolithic tomb, some 100 meters long, is believed to date back to around 3600BC, and is situated atop a chalk ridgeway that overlooks Silbury Hill, Avebury and across to the burial mounds at Windmill Hill. Again, one couldn’t help but feel that the placement of this site was designed to allow a space of performance within the landscape, to view and be viewed by the surrounding sacred sites.

Our experiencing of West Kennet was heightened all the more by the fortunate circumstance of having arrived as the sun began to set, allowing an intense orange glow to permeate the glass skylights, melting away the darkness that would otherwise fill the tomb’s chambers. It would be impossible not to feel awe-struck in a situation like this, where natural elements seem to come together to display the otherwise hidden vitality of a site in all its glory. Even as a sceptic, I could see past the problematics of assigning agency to nature here; the true mystery of the Avebury landscape has to be its ability to coerce you into becoming part of it, to look beyond reason and doubt and to prioritise experience alone as the point from which an understanding of place might be found. In doing so we might be no nearer the historical truth behind these mysterious sites that lay strewn across the Wiltshire countryside but the intensity with which such places act upon us, aesthetically and sensorially, demands a unique kind of veneration, one that exists beyond any prescribed spirituality.

Having reached the final point in our walk, we made the trek back down the ridge and along the main road toward Beckhampton from where our journey had begun. Pairs of headlights sped past us through the dusk as we followed the road leading to the village and I think all were glad to soon find themselves in a log fire warmed dining room, lamenting past travels over hot food and decent ale.

Avebury is special, not only because of its continued spiritual significance or site of seemingly unsolved mystery, but because it demands something from us in order to be seen, felt, heard. Each of the sites relates to another in such a way that I have experienced in no other place. This landscape is ancient, obviously so, and a desire to decode or unravel the deep history that surrounds it is surely something felt by all who visit Avebury. But Avebury seems to require more than this, offering trajectories that run in and between its myriad hills, mounds, trackways, standing stones and barrows, so as to invite the walker inwards, to become part of the landscape. As such, Avebury is a place that becomes excavated at ground level, through perambulation in and between its ancient features. To move through this place is to wade through the mires of a landscape saturated in lore and legend, it really is an area that demands to be explored – my only advice, bring your Wellies!